One of my favourite contemporary novels to teach is Ellen Ullman’s The Bug. I’ve taught it twice now, at Emory as part of “Inventing Languages” and at TRU as part of “Other Minds: Exploring Nonhuman Consciousness in Literature and Film.”

I could relate to it, which isn’t something I’m prone to doing.

The Bug takes place in Silicon Valley in the early 1980s, when programmers were just getting used to arrival of graphical user interfaces and the mouse. The characters are building a database program which will eventually be used to screen airline passengers for security risks, in the months before 9/11. The software’s code has a function called inregion, which checks whether the mouse was inside a particular window. Inregion is a boolean function, either true or false. In the meantime, Ethan, one of the programmers, is having trouble with his code, his girlfriend, the bisexual German systems admin, and so on, and whenever he gets overwhelmed he thinks, or he types, Here. The craving for here is inregion for people, but it offers none of the assurance of the boolean query. Here expands and proliferates. When it is “true,” it covers a physical and mental terrain so vast it feels like nowhere. It’s a shifter, it’s a transitional object.

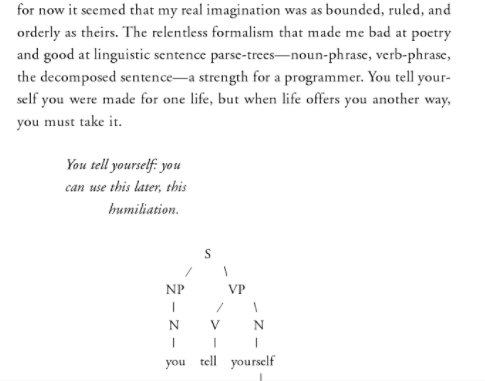

I teach The Bug against the backdrop of an ever expanding push to teach kids to code, and (at least implicitly) not to teach reading or history or philosophy or art. Part of me wants to wail that the move sacrifices the experiential thickness of here to the absolutist logic of inregion. How comforting. Another thing I appreciate about The Bug is how well it mocks those tics of humanist argumentation.[1]The narrator imagines herself at MLA, flattering the professoriate by declaring that her fellow programmers’ incessant punning expressed “the human being’s pent-up need for … Continue reading

I am frankly less concerned by the potential loss of here (which doesn’t save Ethan) than with many readers’ inability to get the determinate, factual part correct. Most of the time, I teach first-year composition. A couple years ago, one of the readings from the textbook was “An Enviro’s Case for Seal Hunt,” by Terry Glavin. The article begins with an image of “a masked man on an ice floe, and a seal lying prone at his feet,” a photo from an advertisement protesting the indigenous Canadian hunting tradition from a British magazine. That’s three levels of embedding. You can’t make sense of that bloody seal except as part of an ad in a trade publication (under multinational capitalism and colonialism, etc., etc.). Glavin described the ad in order to repudiate it, as well as the whole citational chain it was part of. What made him “sick” was not the grisly photo but the way it was being used. Importantly, parsing the argument doesn’t require any particular humanistic chops: You could, if you wanted to, read an op-ed algorithmically, noting (inregion: true/false) the author’s approval or disapproval of each proposition given which conditions. None of this is revelatory. But it is hard for many human readers. When I offered “An Enviro’s Case for Seal Hunt” as an option for a writing assignment, all of the students who chose the article misconstrued it, saying that the author was opposed to the seal hunt (the title notwithstanding). They thought the image of the dead seal was Glavin’s point rather than a foil for it. It was as though they entered a series of embedded loops and exited midway through the first one.

What’s a teacher to do, here? I don’t blame my students and I try not to blame myself. Some of the problem is institutional. Until very recently, class sizes in BC were unconstitutionally large. Some of it is due to academic norms too entrenched for one class to remedy. Reading and writing are taught atomistically, when reading is taught at all. “Citation” is separate from “claim” is separate from “character.” Nevertheless, I am torn between thinking reading should be taught in more of a holistic manner and that it should be more like learning to code. As in: count your loops.

Is reading precision work? The question is ideological. About half of Americanist New Historicism is devoted to the idea that midcentury intellectuals fetishized nuance and paradox within the text in order to distract from the economic and racial oppression around it. I’m not swayed by that argument in general (the New Critics didn’t write The Scarlet Letter), though admittedly there are times when “complexity” and “debate” simply preserve the status quo. If too-close reading is indulgent or worse, how much reading is enough? Recently, the BC Supreme Court ruled that reading a document does not imply understanding it, for legal purposes.[2]“Whether a person has been given an opportunity to read a document is a relatively simple question of fact. However, whether a person has been given an adequate opportunity to understand a … Continue reading

An fMRI study from 2008—I found it because it was, again, in my students’ textbook—posited that a Google search involves complex mental tasks like judgement and decision-making, whereas reading a book in print doesn’t. The authors didn’t actually prove that about reading; the design of their experiment presupposed it.[3]“We wanted to observe and measure only the brain’s activity from those mental tasks required for Internet searching, such as scanning for targeted key words, rapidly choosing from among … Continue reading I am reading too much into it (of course), but the textbook which contained “Enviro’s Case” was called Becoming an Active Reader. This one was called Academic Writing, Real World Topics. Writing (and the real world!) but not reading. How many students caught that?

The problem with teaching reading like coding, though, is the same problem with teaching coding, or any currently valued skill. When we conceive of reading as both detail-oriented and routinizable, we cheapen it by association with women’s work, outsourceable labour, or, of course, actual algorithms. Here retreats, leaving only the bottom line.

References

| ↑1 | The narrator imagines herself at MLA, flattering the professoriate by declaring that her fellow programmers’ incessant punning expressed “the human being’s pent-up need for ambiguity,” even though, she sees now, it was quite the opposite (59). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Whether a person has been given an opportunity to read a document is a relatively simple question of fact. However, whether a person has been given an adequate opportunity to understand a complex document involves a far more complex issue. If the legislature had intended to impose a requirement that a person understand a document it could have said so.” Chen v. West Georgia Ltd. Partnership, 2017 |

| ↑3 | “We wanted to observe and measure only the brain’s activity from those mental tasks required for Internet searching, such as scanning for targeted key words, rapidly choosing from among several alternatives going back to a previous page if a particular search choice was not helpful, and so forth. We alternated this control task—simply reading a simulated page of text—with the Internet-searching task…” (Gary Small and Gigi Vorgan, “Meet Your iBrain,” Scientific American Mind 19.5 [Nov. 2008]). |